Hồi đó tôi tự xưng là Bác sĩ Wanugh-hoo, chuyên gia y học dân tộc của người da đỏ – Jeff Peters kể (thực ra hắn chỉ là tay chuyên bán cao đơn hoàn tán và thuốc ho lẩm cẩm ở các góc phố) – kiếm ăn cũng rất chật vật. Tôi đến thị trấn Fisher Hill mà trong túi chỉ còn năm đô. Tôi mua một chai bia, và vào khách sạn. Đời thấy tươi lên liền khi tôi thấy phòng không bị cúp nước và vỏ bia chất cả chục cái trong góc phòng.

Làm thuốc giả hả? Không dám đâu! Với một chai canh-ki-na, một ít anilin và chai bia đó, tôi chế được cả đống chai thuốc ho mà sau này còn nghe người ta hỏi thăm mua thêm.

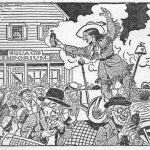

Fisher Hill dòm sơ là tôi biết ngay thuộc loại thành phố bụi bậm, thuốc trị các chứng thiếu vitamin C và tim phổi là cái người ta cần. Tôi bán được chừng hai chục chai, chỉ 50 xu một chai thôi, thì thấy có ai kéo áo phía sau lưng. Tôi biết ngay là ai nên móc túi thủ sẵn đồng năm đô dúi ngay cho thằng cha có đeo ngôi sao cảnh sát đó.

– Có giấy phép bán mấy thứ anh gọi là thuốc này không? – Tay cảnh sát hỏi.

– Không. Bộ còn có cái vụ giấy phép nữa hả – Tôi vờ vịt – Để mai tôi đi xin.

– Còn tôi sẽ nhốt anh đến lúc anh đi xin phép.

Nói vậy chứ nó cũng cho tôi về. Tôi dẹp đồ nghề và lui ngay. Đến nhà, tôi kể với ông chủ nhà trọ. Ông ta bảo:

– Đừng có hòng xin. Bác sĩ Hoskins, người hành nghề duy nhất ở đây, là em rể thị trưởng. Tụi nó không đời nào cho ai bán buôn thuốc men gì đâu.

– Tôi có giấy phép bạn thuốc dạo của bang. Tôi sẽ xin thêm giấy của thành phố nếu cần.

Tôi tới tòa thị sảnh sáng hôm sau. Ông thị trưởng chưa tới. Tôi đành ngồi chờ. Một chàng trẻ tuổi mò đến ngồi cạnh. Tôi nhận ra ngay đó là Andy Tucker, cũng hành nghề bán thuốc lang băm như tôi. Andy hài lòng vì tôi còn nhớ nó. Thằng này làm ăn đàng hoàng, có lương tâm nghề nghiệp và lòng tự trọng. Nó luôn hài lòng với tỷ lệ lời cỡ 300 phần trăm. Biết bao người đã rủ nó làm thuốc giả hoặc bán hạt giống dỏm, nhưng nó luôn giữ đường ngay nẻo chánh.

Hai đứa tôi đi ra ngoài. Tôi than thở với nó về cái liên minh ma quỉ giữa thị trưởng và giới y học. Andy vừa tới đây sáng nay và cũng đang định xoay xở gì đó kiếm ít xu với mớ thuốc của nó. Chúng tôi ngồi nói chuyện hồi lâu, bàn bạc đủ thứ. Vẫn không thấy cho thị trưởng ló mặt tới.

Sáng hôm sau, tôi đang ở nhà trọ thì một viên chức nọ tới lùng sục, đòi gặp bác sĩ đang trọ ở đây. Y nói thẩm phán Banks, kiêm thị trưởng, đang bị bệnh nặng.

– Tôi không phải bác sĩ – tôi đáp – sao anh không mời bác sĩ của thành phố.

– Ồ – y đáp – bác sĩ Hoskins đi khám bệnh xa cả hai chục dậm, mà ông Banks bệnh bất ngờ. Ông ta biểu tôi tới mời ông khám giùm.

– Tôi sẽ tới, nhưng để thăm hỏi thôi – rồi tôi mang theo một chai thuốc và tới tòa thị sảnh, tòa nhà bảnh nhất thành phố.

Ông thị trưởng nằm trên giường, bụng kêu òng ọc om sòm thiếu điều làm người chạy xe ngoài đường phải hoảng hốt tắt máy đậu lại. Một thanh niên đứng cạnh giường cầm ly nước.

– Bác sĩ – ông ta kêu – Tôi bệnh quá. Chắc chết mất. Cứu giùm với bác sĩ ơi!

– Thưa ngài. Tôi không phải học trò Hippocrates, cũng chưa tốt nghiệm trường y nào cả – tôi đáp – tôi đến chỉ để thăm hỏi xem ngài cần gì thôi.

– Rất cảm ơn, bác sĩ Waugh-hoo. Còn đây là cháu tôi, thằng Biddle, nó đang cố giúp tôi bớt đau mà không ăn thua. Ô, Chúa ơi… ô… ô… ô! Ông ta hú lên.

Tôi gật đầu chào Biddle, ngồi xuống cạnh giường và bắt mạch ông thị trưởng, rồi bắt ông ta cho coi lưỡi, vạch mi mắt ông ta lên săm soi một hồi.

– Ông bị bao lâu rồi?

– Mới tối qua – ông ta đáp – Cho tôi thứ thuốc gì đi, bác sĩ.

– Thưa ngài – tôi nói sau khi áp tai nghe phổi trái của ông ta – Ông bị siêu viêm xương đòn phải của cái “hápsikọoc”!

– Chúa ơi! – ông ta rên – rồi phải bôi hay uống cái gì đây?

Tôi cầm lấy mủ và đi ra cửa.

– Bác sĩ đi sao? – ông ta hú lên – Ông đâu thể đi, bỏ mặc tôi chết vì cái vụ siêu… nhiên… sì… cọoc này!

– Bác sĩ Whoa-ha – thằng cháu Biddle lên tiếng – Lòng nhân đạo đâu cho phép ông để người ta như thế.

– Xin lỗi, tôi là Waugh-hoo – tôi trở lại bên giường, vuốt tóc ra đàng sau – Thưa ngài. Chỉ còn một hy vọng. Thuốc chẳng cứu được ngài đâu, tuy thuốc men ngày nay rất hiện đại.

– Đó là hy vọng gì?

– Đó là phương pháp «xacxaparila» !

– Trời, ngài nói gì tôi không hiểu.

– À, đó là lý thuyết của trường phái sáng thế chuyên trị chứng viêm u màng não ảo thế, một phương pháp điều trị tại gia được gọi là liệu pháp xacxaparila!

– Ông biết phương pháp đó không?

– Tôi là một trong những học trò nội trú của Sole Sanhedrims và Ostensible Hooplas mà – tôi «nổ» – Đi qua đâu là người què đi được, người mù thấy được. Tôi là trung gian, giúp người ta phục hồi thiên linh, miên thuật sắc lào. Ngài thấy tôi bán thuốc dạo cho người nghèo, tôi đâu dùng đến phép «xacxaparila»! Thứ đó đâu phải để bán rong ngoài chợ.

– Thế ông chịu giúp tôi không?

– Xin ngài hiểu cho, tôi đi đâu cũng bị giới y học địa phương làm khó dễ. Tôi không hành nghề y. Để giúp ngài, tôi sẽ áp dụng xacxaparila, miễn là ngài đừng đụng tới chuyện giấy phép.

– Được rồi, được rồi! Ông làm ngay đi.

– Thù lao là hai trăm năm mươi đô. Bảo đảm điều trị hai lần là hết.

– Được, tôi sẽ trả. Mạng sống còn quí hơn nhiều.

Tôi ngồi xuống giường và nhìn thẳng vào mắt ông ta.

– Nào – tôi nói – Đừng nghĩ tới bệnh tật nữa. Ông không hề đau xương đau đòn gì cả. Bây giờ ông bắt đầu thấy không có đau đớn gì cả nghe chưa?

– Thấy khá hơn rồi bác sĩ – ông ta nói – Thật đó. Bây giờ nói láo thêm vài câu là tôi không bệnh gì cả là chắc nhảy ngay dậy được.

Tôi đưa tay qua người ông vài lần.

– Nào, bây giờ hết viêm rồi. Bây giờ ông bắt đầu buồn ngủ, không mở mắt nổi nữa. Cơn bệnh đã lui và ông buồn ngủ.

Ông thị trưởng khép mắt lại và bắt đầu ngáy.

– Thấy chưa, ông Tiddle – tôi nói – phép lạ của phương pháp «xacxaparila».

– Tôi tên là Biddle – thằng cháu sửa – Chừng nào điều trị lần nữa, bác sĩ Pooh-hooh?

– Waugh-hoo! Nghe chưa? – tôi nạt lại – Mười một giờ sáng mai tôi trở lại. Cứ cho ông ta ăn uống bình thường. Chào nghe.

Hôm sau tôi trở lại đúng hẹn.

– Chào ông Biddle – tôi lên tiếng ngay khi bước vào – ông Thị trưởng khỏe không?

– Coi bộ khá rồi – thằng cháu ông Thị trưởng đáp.

– Để tôi điều trị cho ông lần nữa. Chắc chắn khỏi thôi. Ông nên nằm dưỡng thêm một hai ngày – tôi nói với tay Thị trưởng – May cho ông là tình cờ tôi đi qua Fisher Hill này chứ không là nguy cho ông rồi. Thôi bây giờ nói chuyện khác cho vui vẻ hơn đi. Thí dụ như chuyện thù lao hai trăm rưỡi của tôi. Đừng trả bằng chi phiếu nghe. Tôi ghét thủ tục ngân hàng lắm.

– Tôi có sẵn đây – ông Thị trưởng móc ví giấu dưới gối ra, đếm đủ năm tờ năm chục đưa cho tôi.

Tôi ký vào phiếu chi và nhận tiền, rồi cẩn thận cất vào túi.

– Bây giờ, ông Thị trưởng chợt nói – mời ngài sĩ quan làm nhiệm vụ – và ông ta nhe răng cười không có vẻ gì bệnh tật cả.

Tên Biddle đặt tay lên vai tôi:

– Ông đã bị bắt, bác sĩ Waugh-hoo, tên thật Peters, vì tội hành nghề y không giấy phép.

– Anh là ai? – Tôi hỏi.

– Để tôi nói – Thị trưởng đáp – Đó là thám tử của Hiệp hội Y học tiểu bang. Anh ta đã theo dõi ông năm thị trấn và tới đây hôm qua. Chúng tôi bày ra kế hoạch này để bắt ông. Hy vọng ông không còn làm trò chữa bệnh vớ vẩn ở quanh đây nữa, ông Phakia ạ. – Rồi ông phá lên cười và ngồi bật dậy – Ông bảo tôi bị cái gì? Cái gì mà siêu viêm rồi ảo thể… lung tung láo lếu vậy. Hà hà… há.

– Thám tử à? – Tôi rên.

– Rất chính xác – Biddle nói – Tôi sẽ đưa ông qua cảnh sát trưởng.

– Đừng hòng! Tôi gào lên rồi lao vào chụp lấy hắn, nhưng lập tức hắn móc đâu ra một khẩu súng chĩa vào cằm tôi. Tôi đành đứng im, hắn lấy còng khóa tay tôi, rồi rút hết tiền trong túi tôi ra.

– Tôi làm chứng – hắn nói – đây chính là những tờ bạc mà tôi với ông đã đánh dấu, ngài Thẩm phán ạ. Tôi sẽ nộp cho cảnh sát trưởng làm bằng và gởi cho ngài biên nhận. Đây sẽ là bằng chứng buộc tội.

– Được rồi, ông Biddle – Thị trưởng nói – Còn bác sĩ Waugh-hoo thử dùng «xacxaparila» gỡ còng ra coi.

– Thưa ngài – tôi nghiêm trang trả lời ông ta – rồi sẽ tới lúc ông phải công nhận «xacxaparila» là hữu hiệu, kể cả trong trường hợp này.

Khi Biddle áp giải tôi ra gần tới cổng, tôi nói:

– Ê, tháo còng ra đi chứ, Andy, kẻo ra tới ngoài gặp người lạ là chết cả đám!

Có gì ngạc nhiên đâu? Biddle chính là Andy Tucker. Kế hoạch này do chính nó bày ra. Nhờ vậy mà tụi tôi có vốn làm ăn tới giờ này đó chứ.

PHẠM VIÊM PHƯƠNG dịch

Nguồn: Y HỌC CHO MỌI NGƯỜI. Số 7 tháng 02.1997

—–

Jeff Peters as a Personal Magnet

Jeff Peters has been engaged in as many schemes for making money as there are recipes for cooking rice in Charleston, S.C.

Best of all I like to hear him tell of his earlier days when he sold liniments and cough cures on street corners, living hand to mouth, heart to heart with the people, throwing heads or tails with fortune for his last coin.

“I struck Fisher Hill, Arkansaw,” said he, “in a buckskin suit, moccasins, long hair and a thirty-carat diamond ring that I got from an actor in Texarkana. I don’t know what he ever did with the pocket knife I swapped him for it.

“I was Dr. Waugh-hoo, the celebrated Indian medicine man. I carried only one best bet just then, and that was Resurrection Bitters. It was made of life-giving plants and herbs accidentally discovered by Ta-qua-la, the beautiful wife of the chief of the Choctaw Nation, while gathering truck to garnish a platter of boiled dog for the annual corn dance.

“Business hadn’t been good in the last town, so I only had five dollars. I went to the Fisher Hill druggist and he credited me for half a gross of eight-ounce bottles and corks. I had the labels and ingredients in my valise, left over from the last town. Life began to look rosy again after I got in my hotel room with the water running from the tap, and the Resurrection Bitters lining up on the table by the dozen.

“Life began to look rosy again…”

“Fake? No, sir. There was two dollars’ worth of fluid extract of cinchona and a dime’s worth of aniline in that half-gross of bitters. I’ve gone through towns years afterwards and had folks ask for ’em again.

“I hired a wagon that night and commenced selling the bitters on Main Street. Fisher Hill was a low, malarial town; and a compound hypothetical pneumocardiac anti-scorbutic tonic was just what I diagnosed the crowd as needing. The bitters started off like sweetbreads-on-toast at a vegetarian dinner. I had sold two dozen at fifty cents apiece when I felt somebody pull my coat tail. I knew what that meant; so I climbed down and sneaked a five dollar bill into the hand of a man with a German silver star on his lapel.

“I … commenced selling the bitters on Main Street.”

“‘Constable,’ says I, ‘it’s a fine night.’

“‘Have you got a city license,’ he asks, ‘to sell this illegitimate essence of spooju that you flatter by the name of medicine?’

“‘I have not,’ says I. ‘I didn’t know you had a city. If I can find it to-morrow I’ll take one out if it’s necessary.’

“‘I’ll have to close you up till you do,’ says the constable.

“I quit selling and went back to the hotel. I was talking to the landlord about it.

“‘Oh, you won’t stand no show in Fisher Hill,’ says he. ‘Dr. Hoskins, the only doctor here, is a brother-in-law of the Mayor, and they won’t allow no fake doctor to practice in town.’

“‘I don’t practice medicine,’ says I, ‘I’ve got a State peddler’s license, and I take out a city one wherever they demand it.’

“I went to the Mayor’s office the next morning and they told me he hadn’t showed up yet. They didn’t know when he’d be down. So Doc Waugh-hoo hunches down again in a hotel chair and lights a jimpson-weed regalia, and waits.

“By and by a young man in a blue necktie slips into the chair next to me and asks the time.

“‘Half-past ten,’ says I, ‘and you are Andy Tucker. I’ve seen you work. Wasn’t it you that put up the Great Cupid Combination package on the Southern States? Let’s see, it was a Chilian diamond engagement ring, a wedding ring, a potato masher, a bottle of soothing syrup and Dorothy Vernon—all for fifty cents.’

“Andy was pleased to hear that I remembered him. He was a good street man; and he was more than that—he respected his profession, and he was satisfied with 300 per cent. profit. He had plenty of offers to go into the illegitimate drug and garden seed business; but he was never to be tempted off of the straight path.

“I wanted a partner, so Andy and me agreed to go out together. I told him about the situation in Fisher Hill and how finances was low on account of the local mixture of politics and jalap. Andy had just got in on the train that morning. He was pretty low himself, and was going to canvass the whole town for a few dollars to build a new battleship by popular subscription at Eureka Springs. So we went out and sat on the porch and talked it over.

“The next morning at eleven o’clock when I was sitting there alone, an Uncle Tom shuffles into the hotel and asked for the doctor to come and see Judge Banks, who, it seems, was the mayor and a mighty sick man.

“‘I’m no doctor,’ says I. ‘Why don’t you go and get the doctor?’

“‘Boss,’ says he. ‘Doc Hoskins am done gone twenty miles in de country to see some sick persons. He’s de only doctor in de town, and Massa Banks am powerful bad off. He sent me to ax you to please, suh, come.’

“‘As man to man,’ says I, ‘I’ll go and look him over.’ So I put a bottle of Resurrection Bitters in my pocket and goes up on the hill to the mayor’s mansion, the finest house in town, with a mansard roof and two cast iron dogs on the lawn.

“This Mayor Banks was in bed all but his whiskers and feet. He was making internal noises that would have had everybody in San Francisco hiking for the parks. A young man was standing by the bed holding a cup of water.

“‘Doc,’ says the Mayor, ‘I’m awful sick. I’m about to die. Can’t you do nothing for me?’

“‘Mr. Mayor,’ says I, ‘I’m not a regular preordained disciple of S. Q. Lapius. I never took a course in a medical college,’ says I. ‘I’ve just come as a fellow man to see if I could be off assistance.’

“‘I’m deeply obliged,’ says he. ‘Doc Waugh-hoo, this is my nephew, Mr. Biddle. He has tried to alleviate my distress, but without success. Oh, Lordy! Ow-ow-ow!!’ he sings out.

“I nods at Mr. Biddle and sets down by the bed and feels the mayor’s pulse. ‘Let me see your liver—your tongue, I mean,’ says I. Then I turns up the lids of his eyes and looks close that the pupils of ’em.

“‘How long have you been sick?’ I asked.

“‘I was taken down—ow-ouch—last night,’ says the Mayor. ‘Gimme something for it, doc, won’t you?’

“‘Mr. Fiddle,’ says I, ‘raise the window shade a bit, will you?’

“‘Biddle,’ says the young man. ‘Do you feel like you could eat some ham and eggs, Uncle James?’

“‘Mr. Mayor,’ says I, after laying my ear to his right shoulder blade and listening, ‘you’ve got a bad attack of super-inflammation of the right clavicle of the harpsichord!’

“‘Good Lord!’ says he, with a groan, ‘Can’t you rub something on it, or set it or anything?’

“I picks up my hat and starts for the door.

“‘You ain’t going, doc?’ says the Mayor with a howl. ‘You ain’t going away and leave me to die with this—superfluity of the clapboards, are you?’

“‘Common humanity, Dr. Whoa-ha,’ says Mr. Biddle, ‘ought to prevent your deserting a fellow-human in distress.’

“‘Dr. Waugh-hoo, when you get through plowing,’ says I. And then I walks back to the bed and throws back my long hair.

“‘Mr. Mayor,’ says I, ‘there is only one hope for you. Drugs will do you no good. But there is another power higher yet, although drugs are high enough,’ says I.

“‘And what is that?’ says he.

“‘Scientific demonstrations,’ says I. ‘The triumph of mind over sarsaparilla. The belief that there is no pain and sickness except what is produced when we ain’t feeling well. Declare yourself in arrears. Demonstrate.’

“‘What is this paraphernalia you speak of, Doc?’ says the Mayor. ‘You ain’t a Socialist, are you?’

“‘I am speaking,’ says I, ‘of the great doctrine of psychic financiering—of the enlightened school of long-distance, sub-conscientious treatment of fallacies and meningitis—of that wonderful in-door sport known as personal magnetism.’

“‘Can you work it, doc?’ asks the Mayor.

“‘I’m one of the Sole Sanhedrims and Ostensible Hooplas of the Inner Pulpit,’ says I. ‘The lame talk and the blind rubber whenever I make a pass at ’em. I am a medium, a coloratura hypnotist and a spirituous control. It was only through me at the recent seances at Ann Arbor that the late president of the Vinegar Bitters Company could revisit the earth to communicate with his sister Jane. You see me peddling medicine on the street,’ says I, ‘to the poor. I don’t practice personal magnetism on them. I do not drag it in the dust,’ says I, ‘because they haven’t got the dust.’

“‘Will you treat my case?’ asks the Mayor.

“‘Listen,’ says I. ‘I’ve had a good deal of trouble with medical societies everywhere I’ve been. I don’t practice medicine. But, to save your life, I’ll give you the psychic treatment if you’ll agree as mayor not to push the license question.’

“‘Of course I will,’ says he. ‘And now get to work, doc, for them pains are coming on again.’

“‘My fee will be $250.00, cure guaranteed in two treatments,’ says I.

“‘All right,’ says the Mayor. ‘I’ll pay it. I guess my life’s worth that much.’

“I sat down by the bed and looked him straight in the eye.

“‘Now,’ says I, ‘get your mind off the disease. You ain’t sick. You haven’t got a heart or a clavicle or a funny bone or brains or anything. You haven’t got any pain. Declare error. Now you feel the pain that you didn’t have leaving, don’t you?’

“‘I do feel some little better, doc,’ says the Mayor, ‘darned if I don’t. Now state a few lies about my not having this swelling in my left side, and I think I could be propped up and have some sausage and buckwheat cakes.’

“I made a few passes with my hands.

“‘Now,’ says I, ‘the inflammation’s gone. The right lobe of the perihelion has subsided. You’re getting sleepy. You can’t hold your eyes open any longer. For the present the disease is checked. Now, you are asleep.’

“The Mayor shut his eyes slowly and began to snore.

“‘You observe, Mr. Tiddle,’ says I, ‘the wonders of modern science.’

“‘Biddle,’ says he, ‘When will you give uncle the rest of the treatment, Dr. Pooh-pooh?’

“‘Waugh-hoo,’ says I. ‘I’ll come back at eleven to-morrow. When he wakes up give him eight drops of turpentine and three pounds of steak. Good morning.’

“The next morning I was back on time. ‘Well, Mr. Riddle,’ says I, when he opened the bedroom door, ‘and how is uncle this morning?’

“‘He seems much better,’ says the young man.

“The mayor’s color and pulse was fine. I gave him another treatment, and he said the last of the pain left him.

“‘Now,’ says I, ‘you’d better stay in bed for a day or two, and you’ll be all right. It’s a good thing I happened to be in Fisher Hill, Mr. Mayor,’ says I, ‘for all the remedies in the cornucopia that the regular schools of medicine use couldn’t have saved you. And now that error has flew and pain proved a perjurer, let’s allude to a cheerfuller subject—say the fee of $250. No checks, please, I hate to write my name on the back of a check almost as bad as I do on the front.’

“‘I’ve got the cash here,’ says the mayor, pulling a pocket book from under his pillow.

“He counts out five fifty-dollar notes and holds ’em in his hand.

“‘Bring the receipt,’ he says to Biddle.

“I signed the receipt and the mayor handed me the money. I put it in my inside pocket careful.

“‘Now do your duty, officer,’ says the mayor, grinning much unlike a sick man.

“Mr. Biddle lays his hand on my arm.

“‘You’re under arrest, Dr. Waugh-hoo, alias Peters,’ says he, ‘for practising medicine without authority under the State law.’

“‘Who are you?’ I asks.

“‘I’ll tell you who he is,’ says Mr. Mayor, sitting up in bed. ‘He’s a detective employed by the State Medical Society. He’s been following you over five counties. He came to me yesterday and we fixed up this scheme to catch you. I guess you won’t do any more doctoring around these parts, Mr. Fakir. What was it you said I had, doc?’ the mayor laughs, ‘compound—well, it wasn’t softening of the brain, I guess, anyway.’

“‘A detective,’ says I.

“‘Correct,’ says Biddle. ‘I’ll have to turn you over to the sheriff.’

“‘Let’s see you do it,’ says I, and I grabs Biddle by the throat and half throws him out the window, but he pulls a gun and sticks it under my chin, and I stand still. Then he puts handcuffs on me, and takes the money out of my pocket.

“And I grabs Biddle by the throat.”

“‘I witness,’ says he, ‘that they’re the same bank bills that you and I marked, Judge Banks. I’ll turn them over to the sheriff when we get to his office, and he’ll send you a receipt. They’ll have to be used as evidence in the case.’

“‘All right, Mr. Biddle,’ says the mayor. ‘And now, Doc Waugh-hoo,’ he goes on, ‘why don’t you demonstrate? Can’t you pull the cork out of your magnetism with your teeth and hocus-pocus them handcuffs off?’

“‘Come on, officer,’ says I, dignified. ‘I may as well make the best of it.’ And then I turns to old Banks and rattles my chains.

“‘Mr. Mayor,’ says I, ‘the time will come soon when you’ll believe that personal magnetism is a success. And you’ll be sure that it succeeded in this case, too.’

“And I guess it did.

“When we got nearly to the gate, I says: ‘We might meet somebody now, Andy. I reckon you better take ’em off, and—’ Hey? Why, of course it was Andy Tucker. That was his scheme; and that’s how we got the capital to go into business together.”

Literature Network » O Henry » The Gentle Grafter » Jeff Peters as a Personal Magnet